In June 2025, the Republican-controlled state legislature of Texas, acting on requests from the Trump administration, began an effort to redraw the congressional map that it had enacted a few years back to elect members to the House of Representatives. The proposed map currently circulating through the legislature would hypothetically pick up five extra seats for the Republicans, giving an advantage to the party ahead of the 2026 midterms. This proposed move has sparked a lot of controversy, with Democratic legislators leaving the state earlier this month to avoid voting on the proposed measure. Texas’s Republican officials are filing litigation to expel the Democrats from their positions, and many states are considering redrawing their maps to give one party or the other more of an advantage ahead of the 2026 midterms. This political tactic is called gerrymandering, and we will discuss what it is, why it is problematic for American democracy, and how it can be resolved.

What is Gerrymandering?

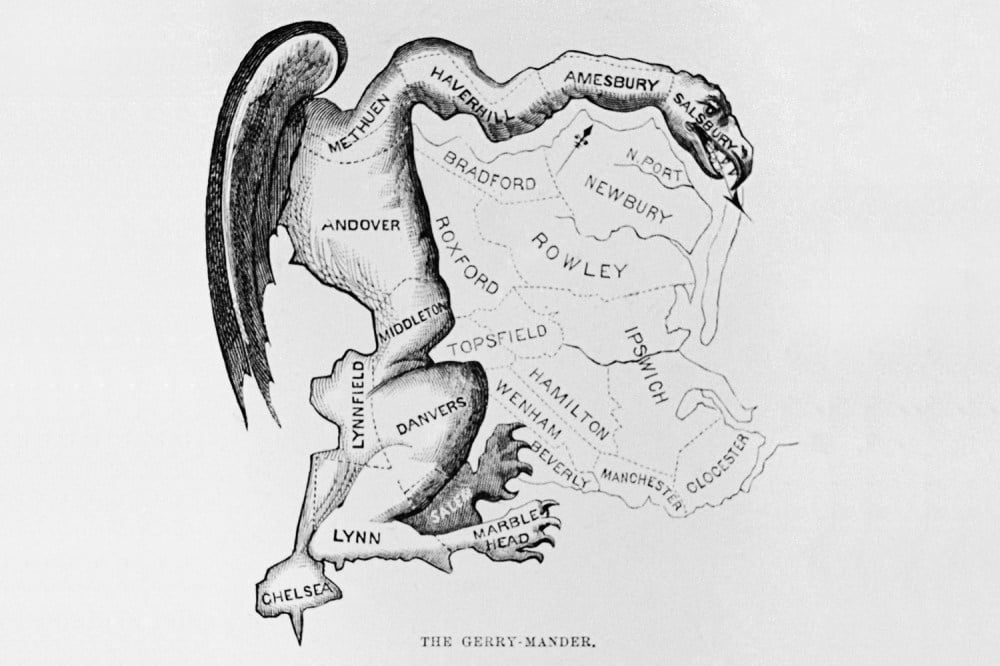

The word “gerrymander” is derived from the combination of the surname of former Vice President Elbridge Gerry and the word salamander. In 1812, Gerry, as governor of Massachusetts, signed into law the creation of a voting district that closely resembled that of a salamander, and that critics felt was meant to favor Gerry’s party. Gerrymandering is defined as manipulating the boundaries of an electoral district to favor a particular political party. As such, gerrymandered districts are often associated with being grotesque-looking and oddly shaped.

The original gerrymander, 1812

Modern examples of the gerrymander. From top to bottom, left to right: North Carolina’s 12th district (2013-2017), Florida’s 5th district (2013-2017), Pennsylvania’s 7th district (2013-2019), Maryland’s 3rd district (2013-2021), North Carolina’s 1st district (2013-2017), Texas’s 33rd district (2013-2021)

Every ten years in the United States, a census is conducted and records population trends in the fifty states. This would determine the number of seats a state would get in the House of Representatives, as that number is determined by population. For instance, in the last census in 2020, owing to population changes from 2010, Texas gained 2 seats while New York lost 1 seat. Redistricting occurs in order to adapt to the changing population of the country and provide an accurate representation of the people.

Changes in the number of House seats after 2020 redistricting cycle. Source: Wikipedia

There is a flaw, however, in how redistricting is conducted in the United States. In most states, the state government is typically responsible for redistricting. This means that states where one party is in near or full control of the entire state government can choose to implement maps that give unfair advantages to one party or the other. This results in a system where politicians are often the ones picking the voters.

Gerrymandering is done primarily in two ways. The first one is called “packing”, where the map is drawn to concentrate the opposing party’s voters into a small number of districts, allowing one party to win more seats in surrounding districts. A good example of this is Texas’s 35th district, a long strip of land connecting the Democratic strongholds of San Antonio and Austin, thereby allowing surrounding districts to become more Republican-leaning. The second one is “cracking”, where the map is drawn to split the opposing party’s voters across many districts so they cannot win a majority anywhere. An example of this occurred in Maryland’s 6th district during the 2010 redistricting cycle, where Republican voters in western Maryland were split among several districts, diluting their power in the 6th. As a result, the previously Republican-leaning 6th district flipped to the Democrats since then and has remained that way ever since.

A visual comparing four competitive districts versus when they are “packed” to favor the blue party and “cracked” to favor the red party. Source: MIT Election Lab

Gerrymandering has been more common since the early 2000s due to the rise of modern mapping software and detailed voter data. One such example arose during the 2010 redistricting cycle, where the Republican State Leadership Committee created a project called REDMAP (Redistricting Majority Project) to increase Republican control of congressional maps. They did this by taking advantage of newly elected Republican majorities in many states, thereby taking control of the redistricting process and drawing maps that elected more Republicans. It paid off big time. In the first election following the 2010 redistricting cycle (2012), Democratic candidates in the House won more votes overall than Republicans, winning 48.8% of the votes versus the Republicans’ 47.7%. However, Republicans took over 53% of the seats in the House (234 out of 435). This can be attributed to the gerrymandering that was done in the swing states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, North Carolina, and Wisconsin, which were competitive or Democratic-leaning at the presidential level but had congressional maps that were drawn to favor Republicans.

North Carolina’s congressional maps, before and after redistricting in 2010. A 7-6 Democratic majority in the House delegation became a 10-3 Republican majority following the 2012 elections as a result of Republicans in the state legislature redrawing the maps to favor themselves.

It is not just Republicans that do gerrymandering, however. Democrats have done it, too. A prominent recent example of this is in the 2022 House elections in Illinois, where Democratic candidates won over 56% of the overall popular vote but ended up winning 14 out of 17 of the state’s congressional districts (82%). This was because the Democratic-controlled state legislature and the Democratic governor had approved maps that benefited Democrats overall. Overall, however, Republicans are more likely to engage in gerrymandering. Most Republican-leaning states currently have maps gerrymandered to give the Republicans an advantage in their state and to limit Democrats from gaining any more seats.

The current state of congressional maps by state, 2025

Gerrymandering has had several effects on American politics. It has made it possible for a party to win a majority of seats in a state despite winning fewer total votes. This was the case in the state of Wisconsin in 2018, where Republican candidates won only 45.6% of the popular vote but ended up winning 5 out of 8 of the state’s congressional districts (62.5%). Gerrymandering also tends to make many districts uncompetitive, leaving parties to abandon many seats entirely and focus their efforts on a select few seats. According to the Cook Political Report, only 43 out of 435 seats in the House of Representatives in the 2024 elections were classified as being competitive. In fact, dozens of congressional incumbents in 2024 ran either unopposed or with no major-party opponent. The lack of competitive districts has led to voters being disincentivized to turn out. After all, if their district is poised to elect the same party over and over again, why bother voting at all?

The Current Situation

Currently, the only form of gerrymandering that is illegal is racial gerrymandering. Drawing districts to dilute the power of voting minorities such as African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latino Americans is prohibited by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution and by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Partisan gerrymandering remains legal at the federal level, and many states have proceeded to gerrymander their maps to favor the ruling party in each of their own.

With Texas redrawing its congressional maps to gain further Republican-leaning seats, other Democratic-leaning states are vying for a response. In California, Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom has proposed getting rid of the state’s independent redistricting commission and making a map that would get rid of several of the state’s Republican members, although this would require a statewide referendum. Other Democratic-leaning states like Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York have considered redrawing their maps, too, although the former two are already heavily gerrymandered enough, and the latter may be legally unattainable. Other Republican-leaning states, such as Florida, Indiana, and Missouri, have also contemplated following in Texas’s lead. This series of events has resulted in a sort of arms race for districts in the House of Representatives. It is an unethical scramble for winning power, largely started by the Republican Party, where its leaders have feared that the party would lose control of the House in 2026 due to President Trump’s unpopularity and the tendency for the ruling party to perform poorly in midterm elections.

What can be done to stop gerrymandering is currently limited. In 2019, the Supreme Court ruled in Rucho v. Common Cause that partisan gerrymandering cannot be challenged in federal courts and has to be handled at the statewide level. Reform efforts, therefore, have to be done at the state level. Independent redistricting commissions have been set up in eight states to take the state legislature out of the redistricting process, thereby limiting the chances of gerrymanders being approved. Still, the vast majority of states opt to have their state legislatures and governors draw the maps. Efforts have been made at the federal level to prohibit gerrymandering, with the “For the People Act” being introduced by congressional Democrats in recent years. However, such efforts have failed, with Republicans largely being the ones voting down measures that would ban gerrymandering.

The ideal system to elect members of the House of Representatives would be to implement a proportional representation (PR) system, eliminating single-member districts entirely. This kind of system already exists in many countries, and would give the appropriate amount of representation to every political party. Unfortunately, under the current Congress and administration, reforms to end gerrymandering are unlikely to pass.

Emil Ordonez, a rising college freshman, is the founder and editor-in-chief of Polinsights. He has been deeply passionate about politics and history since learning every U.S. President at the age of five. He was compelled to start this blog after meeting many people who were misinformed or had become apathetic about how society worked. He hopes to provide factual knowledge and insights that will encourage people, especially the young, to get more engaged in their respective communities. In his free time, he edits for Wikipedia and makes maps for elections. He aspires to work in Congress or even the White House in the future.

Leave a Reply